Epitome of German Mythology. Part 1.

There isn't much known of the mythology of the ancient German tribes. This is an article in which the author tries to make connections with the surviving traditions, superstions and usages with that mythology. His research is based on what other researchers found and on what the clergy wrote about the heathen customs of the ancient Germanic tribes.

(Please note: I

have moved the footnotes from the bottom of the pages directly into the text.

The author refers to his own book vol.I, II and III on 19 occasions in the

footnotes. I have colored these footnotes red like this (See 1.) and made links to the collection of footnotes in a seperate blog.)

What follows are descriptions and tales from an old source:

The

principal sources of German mythology are,

Popular

narratives.

Superstitions

and ancient customs, in which traces of heathen myths, religious ideas and

forms of worship are to be found.

Popular

narratives branch into three classes:

I.

Heroic Traditions (Heldensagen) ;

II.

Popular Traditions (Volkssagen);

III.

Popular Tales (Marchen).

That

they all in common though traceable only in Christian times have preserved much

of heathenism, is confirmed by the circumstance, that in them many beings make

their appearance who incontestably belong to heathenism, viz. those subordinate

beings the dwarfs, water-sprites, etc., who are wanting in no religion which,

like the German, has developed conceptions of personal divinities.

|

| 1. Siegfried slays the Dragon |

The principal sources of German Heroic Tradition are a series of poems, which have been transmitted from the eighth, tenth, but chiefly from the twelfth down to the fifteenth century. These poems are founded, as has been satisfactorily proved, on popular songs, collected, arranged and formed into one whole, for the most part by professed singers. The heroes, who constitute the chief personages in the narrative, were probably once gods or heroes, whose deep-rooted myths have been transmitted through Christian times in an altered and obscured form. With the great German heroic tradition the story of Siegfried and the Nibelunge, this assumption is the more surely founded, as the story, even in heathen times, was spread abroad in Northern song.

|

| 2. Rubezahl, the Giant |

|

| 3.Hänsl and Gretl |

(Many such conjurations and

spells are given by Grimm, D. M. pp. CXXVI-CLIX. 1st edit., and in Mone’s

Anzeiger, also in Altdeutsche Blatter, Bd. ii. etc.).

They are for the most part in rime and rhythmical, and usually conclude with an

invocation of God, Christ and the saints. Their beginning is frequently epic,

the middle contains the potent words for the object of the spell. That many of

these forms descend from heathen times is evident from the circumstance that

downright heathen beings are invoked in them (Erce and Fasolt. See D. M. pp. cxxx-cxxxn. 1st edit. Muller, p. 21.)

.

“A circumstance yet more

striking is, that to the Virgin Mary are transferred a number of pleasing

traditions of Hold and Frouwa, the Norns and Valkyriur. How delightful are

these stories of Mary, and what could any other poesy have to compare with them

! With the kindly heathen characteristics are associated for us a feeling of

the higher sanctity which surrounds this woman. Flowers and plants are named

after Mary, images of Mary are borne in procession and placed in the

forest-trees, in exact conformity with the heathen worship; Mary is the divine

mother, the spinner, and appears as a helpful virgin to all who invoke her. But

Mary stands not alone. In the Greek and the Latin churches a numerous host of

saints sprang up around her, occupying the place of the gods of the second and third

classes, the heroes and wise women of heathenism, and filling the heart,

because they mediate between it and a higher, severer Godhead. Among the saints

also, both male and female, there were manyclasses, and the several cases in

which they are helpful are distributed among them like offices and occupations

For the hero who slew the dragon, Michael or George was substituted, and the

heathen Siegberg was transferred over to Michael; as in France out of Mons

Martis a Mons martyrum (Montmartre) was formed. It is worthy of remark that the

Osseten out of dies Martis (Mardi) make a George s day, and out of dies Veneris

(Vendredi) a Mary s day. Instead of Odin and Freyia, at minnedrinking, St. John

and St. Gertrud were substituted.”)

While

the Scandinavian religion may, even as it has been transmitted to us, be

regarded as a connected

whole, the isolated fragments of German mythology can be considered only as the damaged

ruins of a structure, for the restoration of which the plan is wholly wanting.

But this plan we in great measure possess in the Northern Mythology, seeing

that many of these German ruins are in perfect accordance with it. Hence we may

confidently conclude that the German religion, had it been handed down to us in

equal integrity with the Northern, would, on the whole, have exhibited the same

system, and may, therefore, have recourse to the latter, as the only means left

us of assigning a place to each of its isolated fragments. Although the

similitude of language and manners speaks forcibly in favour of a close

resemblance between the German and Northern mythologies, yet the assumption of

a perfect identity of both religions is, on that account, by no means

admissible ; seeing that the only original authorities for German heathenism,

the Merseburg poems , in the little information supplied by them, show some remarkable

deviations from the religious system of the North (Muller, p. 86. In the Westphalian dialect Wednesday is called

Godenstag, Gaunstag, Gunstag ; in Nether Rhenish, Gudenstag ; in Middleage Netherlandish

or Dutch, Woensdach-, in New Netherl., Woensdag; in Flemish, Goensdag; in Old

Frisic, Wernsdei; in New Fris., Wdnsdey; in Nor. Fris., Winsdei, in Anglo-Sax.,

Wodenes- and Wodnesdag ; in Old Nor., Odinsdagr.)

The

question here naturally presents itself, by what course of events did the

Odinic worship become

spread over the larger portion of Germany and the Netherlands? By Paulus

Diaconus (De Gestis Langobard. i. 8) we are

informed that Wodan was worshipped as a god by all the Germanic

nations. And Jonas of Bobbio (Vita S.

Columbani, in Act. Bened. sec. 2. p. 26) makes mention of

a vessel filled with beer, as an offering to Wodan, among the Suevi (Alamanni) on the Lake of Constance.

Hence it is reasonable to conclude that his worship prevailed especially among

those tribes

which, according to their own traditions and other historic notices, wandered

from north

to south. Whether Wodan was regarded as

a chief divinity by all the German tribes is uncertain,

no traces of his worship existing among the Bavarians; and the name of the

fourth day of

the week after him being found chiefly in the north of Germany, but in no High

German dialect.

The following is Snorri s account of Odin’s course from the Tanais to his final settlement

in Sweden :

“The country to the east of the Tanais (Tanaqvisl)

in Asia was called Asaheim ; but the chief city (borg) in the country was called Asgard.

In this city there was a chief named Odin (Wodan), and there

was a great place of sacrifice (offersted),

etc. At that time the Roman generals were marching over the world and reducing

all nations to subjection; but Odin being foreknowing and possessed

of magical skill, knew that his posterity should occupy the northern half of

the world. He

then set his brothers Ve and Vili over Asgard, but himself, with all the diar (The diar were the twelve chief priests)and

a vast multitude of people, wandered forth, first westwards to Gardariki (The Great and Little Russia of after-times.)

, and afterwards southwards to Saxland (Strictly

the Saxons land ; but by the Northern writers the

name is applied to the whole of Germany, from the Alps in the south to the

Rhine in the west). He had many sons; and

after having reduced under his subjection an extensive kingdom in Saxland, he

placed his sons to defend the country. He afterwards proceeded northwards to

the sea, and took up his abode in an island which is called Odins-ey in Fyen (A singular inaccuracy, Odense (Oftins ey or

rather Oftins ve) being the chief town of Fyen). But when Odin learned that

there were good tracts of land to the east in Gym’s kingdom (See 1), he proceeded thither, and Gylfi

concluded a treaty with him . Odin made his place of residence by the Malar

lake, at the place now called Sigtuna. There he erected a vast temple.

The worship of Thunaer or Donar, the Northern Thor, among the

Germans appears certain only from the Low German formula of renunciation (c forsacho allum dioboles uuercum and uuordum thunaer

ende uuoden ende saxnote ende allem them unholdum the hira genotas sint. -

renounce all the works and words of

the devil, Thunaer and Woden and Saxnot and all those fiends that are their

associates. Massmann,

Abschwbrungsformeln No. 1.) and the name of

the fifth day of the week (Ohg. Donares

tac, Toniris tac ; Mhg.

Donrestac ; Mill. Donresdach ; Nnl. Donderdag ; 0. Fris. Thunresdei, Tornsdei ;

N. Fris. Tongersdei ; Nor.

Fris. Tursdei; A. Sax. Thunres dag; 0. Nor. Thorsdagr.)

|

| 5.Tyr and Fenrir |

The Frisic god Fosite is, according to all probability, the

Scandinavian Forseti (See 3). Of him

it is related that a temple was erected to him in Heligoland, which formerly

bore the name of Fositesland. On the island there was a spring, from which no

one might draw water except in silence. No one might touch any of the animals

sacred to the god, that fed on the island, nor anything else found there. St.

Wilibrord baptized three Frisians in the spring, and slaughtered three of the

animals, for himself and his companions, but had nearly paid with his life for

the profanation of the sanctuary, a crime which, according to the belief of the

heathen, must be followed by madness or speedy death (Alcuini Vita S. Wilibrordi cited by Grimm, D. M. p. 210.) At a

later period, as we are informed by Adam of Bremen, the island was regarded as

sacred by Pirates (De Situ Danise, p.

132. Miiller, p. 88).

Besides the above-named five gods, mention also occurs of three

goddesses, viz. Frigg, the wife of Wodan, who is spoken of by Paulus Diaconus (i. 8) under

the name of Frea (See D. M. p. 276) In the Merseburg poem, where she is called Frua or Friia, she

appears as a sister of Volla, the Northern Fulla. The sixth day of the week is named either

after her or after the Northern goddess Freyia (The

names of the sixth day of the week waver : Ohg. Fria dag, Frijetag ; Mhg.

Fritac, Vriegtag ; Mill.

Vridach ; 0. Fris. Frigendei, Fredei ; N. Fris. Fred-, A. Sax. Frige dag; 0.

Nor. Friadagr, Freyjudagr; S\v. Dan. Fredag.),

but who in Germany was probably called Frouwa ; and the goddess HLUDANA, whom Thorlacius identifies with Hlodyn .

Of the god Saxnot nothing occurs beyond the mention of his name in

the renunciation, which we have just seen. In the genealogy of the kings of Essex a

Seaxneat appears as a son of Woden.

|

| 6. Tuisco |

As the common ancestor of the German nation, Tacitus, on the authority of ancient poems, places the hero or god Tuisco, who sprang from the earth; whose son Mannus had three sons, after whom are named the three tribes, viz. the Ingsevones, nearest to the ocean ; the Herminones, in the middle parts; and the Istsevones.

After

all it is, perhaps, from the several prohibitions, contained in the decrees of

councils or declared

by the laws, that we derive the greater part of our knowledge of German

heathenism. Of these

sources one of the most important is the Indiculus Superstitionum Et Paganiarum,

at the end of a Capitulary of Carloman (A.D.

743), contained in the Vatican MS. No. 577, which is a catalogue of the

heathen practices that were forbidden at the council of Lestines (Liptinse), in the diocese of Cambrai.

Although the Indiculus has been frequently printed, we venture to give it a place here, on account of its importance for German Mythology.

Indiculus

Superstitionum Et Paganiarum.

The sacrilegio ad sepulchra

mortuorum. - "About sacrilege at the graves of the

dead"

The sacrilegio super defunctos

id est dadsisas. - "About sacrilege over the dead, the death-meal"

The spurcalibus in February.

- "About banquets in February"

The casulis id est fanis.

- "About small buildings, that is, shrines"

The sacrilegious per

aecclesias. - "About sacrilegiousness to

churches"

The sacris siluarum quae

nimidas vocant. - "About tree sanctuaries, which they call

nimida's"

The hiis quae faciunt super

petras. - "About the things they do over certain

stones"

The Sacris Mercury, sheet of

Iovis. - "About sacrifices to Mercury or

Jupiter"

The sacrificio quod fit alicui

sanctorum. - "About the sacrificial service for one

or another saint"

The filacteriis et ligaturis.

- "About amulets and bindsels"

The fontibus sacrificiorum.

- "About sacrificing to sources"

The incantation bus.

- "About incantations" (Galdr)

The auguriis sheet avium sheet

equorum sheet bovum stercora sheet sternutationes.

- "About the predictions from

manure

of birds, horses or cattle and sneezing" (Spá)

The divinis sheet sortilogis.

- "About future predictions and throwing fate"

The igne fricato the ligno id

est nodfyr. - "About a fire made of grated wood, what

is called nodfyr"

The cerebro animalium.

- "About the animal brain"

The observatione pagana in

foco, sheet in inchoatione rei alicuius. - "Pagan

perception in the pan, or in the

beginning

of everything"

The incertis locis que colunt

pro sacris. "About places in uncertain place, which

they worship as a sanctuary" (nemetons)

The petendo quod boni vocant

sanctae Mariae. "About the call of the good-natured, who

is seen as Holy Mary"

The feriis quae faciunt Jovi sheet

Mercurio. "About parties that they hold for Jupiter

or Mercury"

The lunae defectione, quod

dicunt Vinceluna. - "About the lunar eclipse they call

Vinceluna"

The tempestatibus et cornibus

et cocleis. - "Over storms, the horns of bulls, and

snails"

The sulcis circa villas.

- "About grooves around farms"

The pagano cursu quem yrias

nominant, scissis pannis sheet calciamentis. -

"About the pagan race they call Yria, with clothes and shoes"

The eo, quod sibi sanctos

fingunt quoslibet mortuos. - "About what they

themselves describe as a holy death"

The simulacro de consparsa

farina. - "About the image of scattered

grains" (grain dummies)

The simulacris the pannis

factis. - "About images made of cloths"

The simulacro quod per campos

porter. - "About the image they carry over the

fields"

The ligneis pedibus sheet

manibus pagano ritual. - "Over wooden feet and

hands to the pagan rite"

The eo, quod credunt, quia

femine lunam comendet, quod possint corda hominum tollere juxta paganos.

- "About

that,

why the women trust the moon, which can elevate the hearts of people to the

Gentiles" (Seiðr)

|

| 7. Indiculus |

From

the popular traditions and tales of Germany a sufficiently clear idea of the

nature of the giants

and dwarfs of Teutonic fiction may be obtained. As in the Northern belief the

giants inhabit

the mountains, so does German tradition assign them dwellings in mountains and caverns.

Isolated mounts, sand-hills or islands have been formed by the heaps of earth

which giant-miaidens have let fall out of their aprons when constructing a dam

or a causeway scattered fragments of rock are from

structures under taken by them in ancient times; and of the huge masses of

stone lying about the country, for the presence of which the common people

cannot otherwise account, it is said that they were cast by giants, or that

they had shaken them out of their shoes like grains of sand. Impressions of

their fingers or other members are frequently to be seen on such stones. Other

traditions tell of giants that have been turned into stone, and certain rocks

have received the appellation of giants clubs (A rock near Bonn is called Fasolt s Keule club). Moors and sloughs

have been caused by the blood that sprang from a giant s wound, as from Ymir’s.

In Germany, too, traces exist of the turbulent elements being

considered as giants. A formula is preserved in which Fasolt is conjured to avert a storm; in

another, Mermeut, who rules over the storm, is invoked. Fasolt

is the giant who figures so often in German middle-age poetry; he was the brother of Ecke, who was himself a divinity of floods and

waves. Of Mermeut nothing further is known. In the German popular tales the devil is

frequently made to step into the place of the giants. Like them he has his abode in rocks , hurls huge

stones, in which the impression of his fingers or other members is often to be seen, causes moors and

swamps to come forth, or has his habitation in them , and raises the whirlwind (Stopke, or Stepke, is in Lower Saxony an

appellation of the devil and of

the whirlwind, from which proceed the fogs that pass over the land. The devil

sits in the whirlwind and rushes howling

and raging through the air. Mark. Sagen, p. 377. The whirlwind is also ascribed

to witches. If a knife be cast

into it, the witch will be wounded and become visible. Schreibers Taschenbuch,

1839, p. 323. Comp. Grimm,

Abergl. 522, 554 ; Mones Anzeiger, 8, 278. (See 4) The spirits that raise storms and hail may be appeased by shaking

out a flour-sack and saying : “Siehe da, Wind, koch ein Mus fur dein Kind “ (See there, Wind, boil a pap for thy child !) ; or by throwing a tablecloth out of the window. Grimm, Abergl. 282.

Like the Wild Huntsman, the

devil on Ash Wednesday hunts the wood-wives. Ib. 469, 914. (See 5)

According to a universal tradition, compacts are frequently made

with the devil, by which he is bound to complete a building, as a church, a house, a barn, a

causeway, a bridge or the like within a certain short period; but by some artifice, through which the

soul of the person, for whom he is doing the work, is saved, the completion of the undertaking is

prevented. The cock, for instance, is made to crow; because, like the giants and dwarfs, who shun the

light of the sun, the devil also loses his power at the break of day. In being thus deceived and

outwitted, he bears a striking resemblance to the giants, who, though possessing prodigious

strength, yet know not how to profit by it, and therefore in their conflicts with gods and

heroes always prove the inferior.

While in the giant-traditions and tales of Germany a great degree

of uniformity appears, the belief in dwarfs displays considerable vivacity and variety ; though no other

branch of German popular story exhibits such a mixture with the ideas of the neighbouring

Kelts and Slaves. This intermingling of German and foreign elements appears particularly

striking on comparing the German and Keltic elf-stories, between which will be found a

strong similitude, which is hardly to be explained by the assumption of an original resemblance

independent of all intercommunication. Tradition assigns to the dwarfs of Germany,

as the Eddas to those of the North, the interior of the earth, particularly rocky caverns, for

a dwelling. There they live together as a regular people, dig for ore, employ

themselves in smith s work, and collect treasures. Their activity is of a

peaceful, quiet character, whence they are distinguished as the still folk (the

good people, the guid neighbours] ; and because it is practised in secret, they

are said to have a tarncap, or tarnmantle (From

Old Saxon dernian, A. S. dyrnan, to conceal. With the dwarfs the sun rises at

midnight. Grimm, D. M. p. 435.), or mistmantle, by which they can make

themselves invisible. For the same reason they are particularly active at

night.

The dwarfs in general are, as we have seen, the personification of

the hidden creative powers, on whose efficacy the regular changes in nature depend. This idea

naturally suggests itself both from the names borne by the dwarfs in the Eddas, and from the myths

connected with them. These names denote for the most part

either activity in general, or individual natural phenomena, as the phases

of the moon, wind, etc. The activity of the dwarfs, which popular tradition

symbolically signifies

by smith’s work, must be understood as elemental or cosmical. It applies

particularly to the

thriving of the fruits of the earth. We consequently frequently find the dwarfs

busied in helping men in their agricultural labours, in getting in the harvest,

making hay and the like, which is merely a debasement of the idea that, through

their efficacy, they promote the growth and maturity of the fruits of the

earth. Tradition seems to err in representing the dwarfs as thievish on such

occasions, as stealing the produce from the fields, or collecting the

thrashed-out corn for themselves; unless such stories are meant to signify that

evil befalls men, if they offend those beneficent beings, and thereby cause

them to suspend their efficacy, or exert it to their prejudice. The same

elemental powers which operate on the fruits of the earth also exercise an

influence on the well-being of living creatures. Well-known and wide-spread is

the tradition that the dwarfs have the power, by their touch, their breathing,

and even by their look, to cause sickness or death to man and beast.

That which

they cause when they are offended they must also be able to remedy. Apollo, who

sends the pestilence, is at the same time the healing god. Hence to the dwarfs

likewise is ascribed a knowledge of the salutary virtues of stones and plants.

In the popular tales we find them saving from sickness and death ; and while

they can inflict injury on the cattle, they often also take them under their

care. The care of deserted and unprotected children is also ascribed to them,

and in heroic tradition they appear as instructors ( Of this description was Regin, the instructor of Sigurd.). At the

same time it cannot be denied that tradition much more frequently tells a

widely different tale, representing them as kidnapping the children of human

mothers and substituting their own changelings, dickkopfs or kielkropfs. These

beings are deformed, never thrive, and, in spite of their voracity, are always

lean, and are, moreover, mischievous. But that this tradition is a

misrepresentation, or at least a part only, of the

original one, is evident from the circumstance, that when the changeling is

taken back the mother

finds her own child again safe and sound, sweetly smiling, and as it were

waking out of a deep

sleep. It had, consequently, found itself very comfortable while under the care

of the dwarfs, as they themselves also declare, that the children they steal

find better treatment with them than with their own parents. By stripping this

belief of its mythic garb, we should probably find the sense to be, that the

dwarfs take charge of the recovery and health of sick and weakly children.

Hence it may also be regarded as a perversion of the ancient belief, when it is

related that women are frequently summoned to render assistance to dwarf-wives

in labour ; although the existence of such traditions may be considered as a

testimony of the intimate and friendly relation in which they stand to mankind.

But if we reverse the story and assume that dwarf-wives are present at the

birth of a human child, we gain an appendage to the Eddaic faith that the Norns,

who appeared at the birth of children, were of the race of dwarfs. In the

traditions it is, moreover, expressly declared that the dwarfs take care of the

continuation and prosperity of families. Presents made by them have the effect

of causing a race to increase, while the loss of such is followed by the

decline of the family ; for this indicates a lack of respect towards these beneficent

beings, which induces them to withdraw their protection. The anger of the

dwarfs, in any way roused, is avenged by the extinction of the offender’s race.

|

| 8. Dwarf |

We

have here made an attempt, out of the numerous traditions of dwarfs, to set

forth, in a prominent

point of view, those characteristics which exhibit their nobler nature, in the supposition

that Christianity may also have vilified these beings as it has the higher

divinities. At the

same time it is not improbable that the nature of the dwarfs, even in heathen

times, may have had

in it something of the mischievous and provoking, which they often display in

the traditions. Among

the wicked tricks of the dwarfs one in particular deserves notice that they lay

snares for young

females and detain them in their habitations, herein resembling the giants,

who, according to

the Edda's, strive to get possession of the goddesses. If services are to be

rendered by them, a pledge must be exacted from them, or they must

be compelled by force; but if once overcome, they

prove faithful servants and stand by the heroes in their conflicts with the

giants, whose natural

enemies they seem to be, though they are sometimes in alliance with them.

Popular

tradition designates the dwarfs as heathens, inasmuch as it allows them to have

power only

over unbaptized children. It gives us further to understand that this belief is

of ancient date, when

it informs us that the dwarfs no longer possess their old habitations. They

have emigrated, driven

away by the sound of church bells, which to them, as heathenish beings, was

hateful, or because

people were malicious and annoyed them, that is, no longer entertained the same

respect for

them as in the time of heathenism. But that this faith was harmless, and could

without prejudice

exist simultaneously with Christianity, appears from the tradition which

ascribes to the dwarfs

Christian sentiments and the hope of salvation (Dwarfs go to church. Grimm, D. S. No. 23, 32. Kobolds are Christians, sing

spiritual songs, and hope to be saved, Ib, i, pp. 112, 113, Miiller, p. 342.)

|

| 9. Norns |

The Northern conception of the Norns is rendered more complete by numerous passages in the Anglo-Saxon and Old-Saxon writers. In Anglo-Saxon poetry Wyrd manifestly occupies the place of Urd , the eldest Norn, as the goddess of fate, who attends human beings when at the point of death; and from the Codex Exoniensis we learn that the influence of the Norns in the guiding of fate is metaphorically expressed as the weaving of a web, as the juoipai and parcse are described as spinners.

( Me haet Wyrd gewaef. - That

Wyrd wove for me. (Cod.Exon.p.355, 1.)

Wyrd oft nered. - Wyrd

oft preserves

unfaegne eorl, - an

undoom’d man,

bonne his elleu dean, - when

his valour avails. (Beowulf, 1139.)

Him waes Wyrd - To him was Wyrd

ungemete neah. - Exceedingly

near. (Ib. 4836.)

Thiu uurd is at handum. - The

Wurd is at hand. (Heliand, p. 146, 2.)

Thiu uurth nahida thuo, - The

Wurth then drew near,

mari maht godes. - the great might of

God. (Ib. 163, 16.)

(In an Old High German gloss

also we find wurt, fatum. (Graff, i. p. 992.) The English and Scotch have

preserved the word the longest, as in the weird sisters of Macbeth and Gawen

Douglas s Virgil ; the weird elves in Warner’s Albion’s England ; the weird

lady of the woods in Percy’s Reliques. (See Grimm, D. M. pp. 376-378 for other instances.)

Thus,

too, does the poet of the Heliand personify Wurth, whom, as a goddess of death,

he in like

manner makes an attendant on man in his last hour.

We

find not only in Germany traditions of Wise Women, who, mistresses of fate, are

present at

the birth of a child ; but of the Keltic fairies it is also related that they

hover about mortals as guardian

spirits, appearing either three or seven or thirteen together nurse and tend

new-born children,

foretell their destiny, and bestow gifts on them, but among which one of them

usually mingles

something evil. Hence they are invited to stand sponsors, the place of honour

is assigned them

at table, which is prepared with the greatest care for their sake. Like the

Norns, too, they spin.

Let

us now endeavour to ascertain whether among the Germans there exist traces of a

belief in the

Valkyriur. In Anglo-Saxon the word wselcyrige (wselcyrie) appears as an equivalent to necis arbiter,

Bellona, Alecto, Erinnys, Tisiphone; the pi. vselcyrian toparcce, venefica-,

and Anglo- Saxon

poets use personally the nouns Hild and Gud, words answering to the names of

two Northern

Valkyriur, Hildr and Gunnr (comp. hildr,

pugna; gunnr, proelium, bellum). In the first Merseburg

poem damsels, or idisi, are introduced, of

whom: ”some fastened fetters, some stopt

an army, some sought after bonds”; and therefore perform functions having

reference to war; consequently are to be regarded as Valkyriur. We have still a superstition to notice, which in

some respects seems to offer a resemblance to the belief in the Valkyriur,

although in the main it contains a strange mixture of senseless,

insignificant stories. We allude to the belief in witches and their nightly meetings. The belief in magic, in evil magicians

and sorceresses, who by means of certain arts are enabled to injure their fellow-creatures, to

raise storms, destroy the seed in the earth, cause sickness to man and beast is of remote antiquity. (We subjoin the principal denominations of magicians and

soothsayers, as affording an insight into their several modes of operation. The

more general names are : divini, magi,

harioli, vaticinatores, etc. More special ippellations are : sortilegi (sortiarii,),

diviners by lot; inicmtatores,

enchanters ; somniorum conjectores, interpreters of dreams, cauculatores and

coclearii, diviners by offering-cups

(comp. Du Fresne subvoce, and Indie. Superst. c. 22); haruspices, consulters

of entrails (Capitul. vn. 370, Legg.

Liutprandi vi. 30; comp. Indie, c. 16, and the divining from human sacrifices.

Procop. de B. G. 2. 25); auspices (Ammian.

Marcel. 14. 9) ; obligatores, tiers of strings or ligatures (for the cure of

diseases) ; tempestarii, or immissores tempestatum,

raisers of storms.)

|

| 10.Valkyrie |

It is found in the East and among the Greeks and Romans; it was

known also to the Germans and Slaves in the time of their paganism, without their having

borrowed it from the Romans. In it there is nothing to be sought for beyond what appears on the

surface, viz. that low degree of religious feeling, at which belief supposes effects from unknown

causes to proceed from super natural agency, as from persons by means of spells, from herbs,

and even from an evil glance a degree which can subsist simultaneously with the

progressing religion, and, therefore, after the introduction of Christianity, could long prevail, and in part

prevails down to the present day. Even in the time of heathenism it was, no

doubt, a belief that these sorceresses on certain days and in certain places

met to talk over their arts and the application of them, to boil magical herbs,

and for other evil purposes. For as the sorcerer, in consequence of his occult

knowledge and of his superiority over the great mass of human beings, became,

as it were, isolated from them, and often harboured hostile feelings towards

them, he was consequently compelled to associate with those who were possessed

of similar power. It must, however, be evident that the points of contact are

too few to justify our seeing the ground of German belief in witch-meetings in

the old heathen sacrificial festivals and assemblies. And why should we be at

the pains of seeking an historic basis for a belief that rests principally on

an impure, confused deisidaimonia, which finds the supernatural where it does

not exist? That mountains are particularly specified as the places of assembly,

arises probably from the circumstance that they had been the offering-places of

our forefathers; and it was natural to assign the gatherings of the witches to

known and distinguished localities

(The

most celebrated witch-mountain is the well-known Bracken (Blocksberg} in the

Harz ; others, of which mention occurs, are the ffuiberg near Halberstadt; in

Thuringia the Horselberg near Eisenach, or the Inselberg near Schmalkalde; in

Hesse the Bechelsberg or Bechtelsberg near Ottrau; in Westphalia the Koterberg

near Corvei, or the Weckingsstein near Minden; in Swabia, in the Black Forest,

at Kandel in the Brisgau, or the Heuberg near Balingen; in Franconia the

Kreidenberg near Wiirzburg, and the Staffelstein near Bamberg; in Alsace the Bischenberg

and Bilchelberg. The Swedish trysting-place is the Blakulla (according to Ihre,

a rock in the sea between Smaland and Gland, literally the Black Mountain), and

the Nasajjall m Norrland. The Norwegian witches also ride to the Blaakolle, to

the Dovrefjeld, to the Lyderhorn near Bergen, to Kiarru, to Vardo and Domen in

Finmark, to Troms (i. e. Trommenfjeld), a mountain in the isle of Tromso, high

up in Finmark. The Neapolitan streghe (striges) assemble under a nut-tree near

Benevento. Italian witchmountains are: the Barco di Ferrara, the Paterno di

Bologna, Spinato della Mirandola, Tossale di Bergamo and La Croce del

Pasticcio, of the locality of which I am ignorant. In France the Puy de Dome,

near Clermont in Auvergne, is distinguished. (Grimm, D. M. p. 1004.) In

Lancashire the witches assembled at Malkin Tower by the side of “ the mighty

Pendle”, of whom the same tradition is current relative to the transforming of

a man into a horse by means of a bridle, as we find in (see 6); also that of striking off a hand (see 7, and 8). See Roby's Popular

Traditions of England, vol. ii. pp. 211-253, edit. 1841.). Equally natural was it that the witches should proceed to the

place of assembly through the air, in an extraordinary manner as on he-goats,

broomsticks (On their way to the Blocksberg,

Mephistopheles says to Faust : “Verlangst du nicht nach einem Besenstiele? Ich

wiinschte mir den allerderbsten Bock. Dost thou not long for a broomstick? I

could wish for a good stout he-goat.“), oven-forks and other utensils.

|

| 11. Witches |

After having thus briefly noticed the gods, the giants, the

dwarfs, etc., there remains for consideration a series of subordinate beings, who are confined to

particular localities, having their habitation in the water, the forests and woods, the fields and in

houses, and who in many ways come in contact with man.

A

general expression for a female demon seems to have been minne, the original

signification of which

was, no doubt, woman. The word is used to designate female water-sprites and

woodwives. Holde

is a general denomination for spirits, both male and female, but occurs

oftenest in composition,

as brunnenholden, wasserholden (spirits

of the springs and waters). There are no bergholden

or waldholden (mountain-holds,

forest-holds), but dwarfs are called by the diminutive holdechen. The

original meaning of the word is bonus genius, whence evil spirits are designated

unholds.

.

The

name of Bilwiz (also written Pilwiz,

Pilewis, Buiweeks) is attended with some obscurity. The feminine

form Bulwechsin also occurs. It denotes a good, gentle being, and may either,

with Grimm, be rendered by tequum sciens, aquus, bonus , or with Leo by the

Keltic bilbheith, bilbhith (from bil,

good, gentle, and bheith or bhith, a being) . Either of these derivations

would show that the name was originally an appellative ; but the traditions

connected with it are so obscure and varying, that they hardly distinguish any

particular kind of sprite. The Bilwiz shoots like the elf, and has shaggy or

matted hair (Bilwitzen (bilmitzen)

signifies to tangle or mat the hair. Muller, p. 367).

In the latter ages, popular belief, losing the old nobler idea of

this supernatural being, as in the case of Holla and Berchta, retained the

remembrance only of the hostile side of its character. It appears,

consequently, as a tormenting, terrifying, hair- and beardtangling, grain-cutting

sprite, chiefly in a female form, as a wicked sorceress or witch. The tradition

belongs more particularly to the east of Germany, Bavaria, Franconia, Voigtland

and Silesia. In Voigtland the belief in the bilsen- or bilver-schnitters, or

reapers, is current. These are wicked men, who injure their neighbours in a

most unrighteous way: they go at midnight stark naked, with a sickle tied on

their foot, and repeating magical formula, through the midst of a field of corn

just ripe. From that part of the field which they have cut through with their

sickle all the corn will fly into their own barn. Or they go by night over the

fields with little sickles tied to their great toes, and cut the straws,

believing that by so doing they will gain for themselves half the produce of

the field where they have cut.

The

Schrat or Schratz remains to be mentioned. From Old High German glosses, which

translate scratun

by pilosi, and waltschrate by satyrus, it appears to have been a spirit of the

woods. In the popular

traditions mention occurs of a being named Jüdel, which disturbs children and

domestic animals.

When children laugh in their sleep, open their eyes and turn, it is said the

Jüdel is playing with

them. If it gets entrance into a lying-in woman’s room, it does injury to the

new-born child. To

prevent this, a straw from the woman’s bed must be placed at every door, then

no Jüdel nor spirit

can enter. If the Jüdel will not otherwise leave the children in quiet,

something must be given

it to play with. Let a new pipkin be bought, without any abatement of the price

demanded; put

into it some water from the child's bath, and set it on the stove. In a few

days the Jüdel will have

splashed out all the water. People also hang egg-shells, the yolks of which

have been blown into

the child s pap and the mother s pottage, on the cradle by linen threads, that

the Jüdel may play

with them instead of with the child. If the cows low in the night, the Jüdel is

playing with them.

But

what are the Winseln ? We are informed that the dead must be turned with the

head towards

the east, else they will be

terrified by the Winseln, who wander hither from the west.

Of the several kinds of spirits, which we classify according to the locality and the elements in which they have their abode, the principal are the demons of the water or the Nixen (The male water-sprite is called nix;, the female nixe. Comp. Ohg. nichus, crocodilus ; A. S. nicor, pi. niceras ; Sw. neck ; Dan. riok. Hnikarr and HnikutJr are names of Odin). Their form is represented as resembling a human being, only somewhat smaller. According to some traditions, the Nix has slit ears, and is also to be known by his feet, which he does not willingly let be seen. Other traditions give the Nix a human body terminating in a fishtail, or a complete fishsform. They are clothed like human beings, but the water-wives may be known by the wet hem of their apron, or the wet border of their robe. Naked Nixen, or hung round with moss and sedge, are also mentioned. Like the dwarfs, the water-sprites have a great love of dancing. Hence they are seen dancing on the waves, or coming on land and joining in the dance of human beings. They are also fond of music and singing. From the depths of a lake sweetly fascinating tones sometimes ascend, oftentimes the Nixen may be heard singing. Extraordinary wisdom is also ascribed to them, which enables them to foretell the future (That water-sprites have the gift of prophecy has been the belief of many nations. We need only remind the reader of Nereus and Proteus). The water-wives are said to spin. By the rising, sinking, or drying up of the water of certain springs and ponds caused, no doubt, by the Nix the inhabitants of the neighbourhood judge whether the seasons will be fruitful or the contrary. Honours paid to the water-spirits in a time of drought are followed by rain, as any violation of their sacred domain brings forth storm and tempest (If stones are thrown into the Mummelsee, the serenest sky becomes troubled and a storm arises. Grimm, D. S. No. 59. The belief is probably Keltish. Similar traditions are current of other lakes, as of theLake of Pilatus, of Camarina in Sicily, etc.). They also operate beneficially on the increase of cattle. They possess flocks and herds, which sometimes come on land and mingle with those of men and render them prolific.

|

| 12. Nixen |

Tradition also informs us that these beings exercise an influence over the lives and health of human beings. Hence the Nixen come to the aid of women in labour; while the common story, as in the case of the dwarfs, asserts the complete reverse. The presence of Nixen at weddings brings prosperity to the bride; and new-born children are said to come out of ponds and springs; although it is at the same time related that the Nixen steal children, for which they substitute changelings. There are also traditions of renovating springs (Jungbrunnen), which have the virtue of restoring the old to youth. (Thus the rugged Else, Wolfdietrich s beloved, bathed in such a spring and came forth the beautiful Sigeminne. Muller, p. 373.) The water-sprites are said to be both covetous and bloodthirsty. This character is, however, more applicable to the males than to the females, who are of a gentler nature, and even form connections with human beings, but which usually prove unfortunate. Male water-sprites carry off young girls and detain them in their habitations, and assail women with violence.

The watersprite suffers no one from wantonness forcibly to enter his dwelling, to examine it, or to diminish its extent. Piles driven in for an aqueduct he will pull up and scatter; those wrho wish to measure the depth of a lake he will threaten; he frequently will not endure fishermen, and bold swimmers often pay for their temerity with their lives. If a service is rendered to the watersprite, he will pay for it no more than he owes ; though he sometimes pays munificently; and for the wares that

he buys, he will bargain and haggle, or pay with old perforated coin. He treats even his relations with cruelty. Water-maidens, who have staid too late at a dance, or other water-sprites, who have intruded on his domain, he will kill without mercy : a stream of blood that founts up from the water announces the deed. Many traditions relate that the water-sprite draws persons down with his net, and murders them; that the spirit of a river requires his yearly offering, etc. To the worship of water-sprites the before-cited passage from Gregory of Tours bears ample witness.

The prohibitions, too, of councils against the performance of any heathen rites at springs, and particularly against burning lights at them, have, no doubt, reference to the water-sprites. In later Christian times some traces have been preserved of offerings made to the demons of the water. Even to the present time it is a Hessian custom to go on the second day of Easter to a cave on the Meisner (A chain of hills in Electoral Hesse), and draw water from the spring that flows from it, when flowers are deposited as an offering (The Bavarian custom also of throwing a man wrapped in leaves or rushes into the water on Whit Monday may have originated in a sacrifice to appease the water-sprite). Near Louvain are three springs, to which the people ascribe healing virtues. In the North it was a usage to cast the remnants of food into waterfalls. Rural sprites cannot have been so prominent in the German religion as water-sprites, as they otherwise would have acted a more conspicuous part in the traditions.

The Osnabruck popular belief tells of a Tremsemutter, who goes among the corn and is feared by the children. In Brunswick she is called the Kornweib (Cornwife). When the children seek for cornflowers, they do not venture too far in the field, and tell one another about the Cornwife who steals little children. In the Altmark and Mark of Brandenburg she is called the Roggenmohme (From roggen, rye, and muhme, aunt, cousin), and screaming children are silenced by saying :”Be still, else the Roggenmohine with her long, black teats will come and drag thee away!“

Or, according to other relations, “with her black iron teats”. By others she is called Rockenmor, because like Holda and Berchta she plays all sorts of tricks with those idle girls who have not spun all off from their spinning-wheels (Rocken) by Twelfth day. Children that she has laid on her black bosom easily die. In the Mark they threaten children with the Erbsenmuhme (From Erbsen, peas), that they may not feast on the peas in the field. In the Netherlands the Long Woman is known, who goes through the corn-fields and plucks the projecting ears. In the heathen times this rural or field sprite was, no doubt, a friendly being, to whose influence the growth and thriving of the corn were ascribed (Adalbert Kuhn, who in the collecting of German popular traditions is indefatigable, makes us acquainted with another female being, who bears a considerable resemblance to Holda, Berchta and others of that class, and is called the Murraue. See more of her in, see 9).

Spirits inhabiting the forests are mentioned in the older authorities, and at the present day people know them under the appellations of Waldleute (Forest-folk), Holzleute (Wood-folk), Moosleute (Moss-folk), Wilde Leute (Wild folk) (The appellation of Schrat is also applicable to the Forestsprites. The Goth, skohsl (Sainovtov) is by Grimm (D. M. p. 455) compared with the 0. Nor. Skogr (forest), who thence concludes that it was originally a forest-sprite. Jornandes speaks of sylvestres homines, quos faunos ficarios vocant.)

The traditions clearly distinguish the Forest-folk from the Dwarfs, by ascribing to them a larger stature, but have little more to relate concerning them than that they stand in a friendly relation to man, frequently borrow bread and household utensils, for which they make requital but are now so disgusted with the faithless world that they have retired from it. Such narratives are in close analogy with the dwarf-traditions, and it is, moreover, related of the females, that they are addicted to the ensnaring and stealing of children (The wood-wives (Holzweibel) come to the wood-cutters and ask for something to eat, and will also take it out of the pots ; though they remunerate for what they have taken or borrowed in some other way, frequently with good advice. Sometimes they will help in the labours of the kitchen or the wash; but always express great dread of the Wild Huntsman, who persecutes them. Grimm, D. M. p. 452.). On the Saale they tell of a Buschgrossmutter (Bush-grandmother) and her Moosfräulein (Moss-damsels).

The Buschgrossmutter seems almost a divine being of heathenism, holding sway over the Forest-folk; as offerings were made to her. The Forest-wives readily make their appearance when the people are baking bread, and beg to have a loaf baked for them also, as large as half a millstone, which is to be left at an appointed spot. They afterwards either compensate for the bread, or bring a loaf of their own batch, for the ploughmen, which they leave in the furrow or lay on the plough, and are exceedingly angry if any one slights it. Sometimes the Forest-wife will come with a broken wheelbarrow, and beg to have the wheel repaired. She will then, like Berchta, pay with the chips that fall, which turn to gold; or to knitters she gives a clew of thread that is never wound off. As often as any one twists the stem of a sapling, so that the bark is loosed, a Forestwife must die. A peasant woman, who had given the breast to a screaming forest-child, the mother rewarded with the bark on which the child lay. The woman broke off a piece and threw it in her load of wood: at home she found it was gold. Like the dwarfs, the Forest-wives are dissatisfied with the present state of things. In addition to the causes already mentioned, they have some particular reasons. The times, they say, are no longer good since folks count the dumplings in the pot and the loaves in the oven, or since they piped the bread, and put cumin into it. (To pipe the bread (das Brot pipen) is to impress the points of the fingers into the loaf, as is usual in most places. Perhaps the Forest-wives could not carry off piped bread. From a like cause they were, no doubt, averse to the counting. Whether the seasoning with cumin displeased them merely as being an innovation, or for some hidden cause, we know not, but the rime says:

|

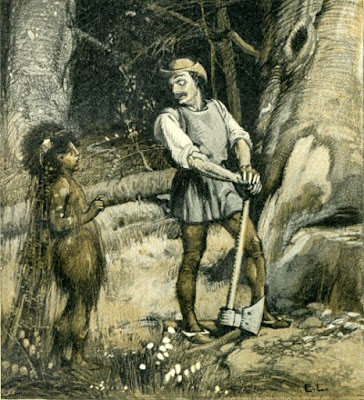

| 13. Bushgrandmother |

Kummelbrot unser Tod! Cumin-bread our death!

Kummelbrot macht Angst und Noth ! Cumin-bread makes pain and affliction !

Hence their precepts: Peel no tree, relate no dream, pipe no bread, or bake no cumin in bread, so will God help thee in thy need. A Forest-wife, who had just tasted a new-baked loaf, ran off to the forest screaming aloud: They’ve baken for me cumin-bread, that on this house brings great distress! And the prosperity of the peasant was soon on the wane, so that at length he was reduced to abject poverty

Little Forest-men, who have long worked in a mill, have been scared away by the miller''s men leaving clothes and shoes for them. It would seem that by accepting clothes these beings were fearful of breaking the relation subsisting between them and men.

We shall see presently that the domestic sprites act on quite a different principle. We have still a class of subordinate beings to consider, viz. the domestic sprites or Goblins (Kobolde). Numerous as are the traditions concerning these beings, there seems great reason to conclude that the belief in them, in its present form, did not exist in the time of heathenism; but that other ideas must have given occasion to its development. The ancient mythologic system has in fact no place for domestic sprites and goblins. Nevertheless, we believe that by tracing up through popular tradition, we shall discern forms, which at a later period were comprised under the name of Kobolds (Muller, p. 381. According to the Swedish popular belief, the domestic sprite had his usual abode in a tree near the house. Muller, p. 382. Grimm, D. M. p. 479.)

The domestic sprites bear a manifest resemblance to the dwarfs. Their figure and clothing are represented as perfectly similar; they evince the same love of occupation, the same kind, though sometimes evil, nature. We have already seen that the dwarfs interest themselves in the prosperity of a family, and in this respect the Kobolds may be partially considered as dwarfs, who, for the sake of taking care of the family, fix their abode in the house. In the Netherlands the dwarfs are called Kaboutermannekens, that is, Kobolds . The domestic sprite is satisfied with a small remuneration, as a hat, a red cloak, and party-coloured coat with tingling bells. Hat and cloak he has in common with the dwarfs. It may probably have been a belief that the deceased members of a family tarried after death in the house as guardian and succouring spirits, and as such, a veneration might have been paid them like that of the Romans to their lares. It has been already shown that in the heathen times the departed were highly honoured and revered, and we shall presently exemplify the belief that the dead cleave to the earthly, and feel solicitous for those they have left behind. Hence the domestic sprite may be compared to a lar familiaris, that participates in the fate of its family. It is, moreover, expressly declared in the traditions that domestic sprites are the souls of the dead, and the White Lady who, through her active aid, occupies the place of a female domestic sprite, is regarded as the ancestress of the family, in whose dwelling she appears. (Kobolds are the souls of persons that have been murdered in the house. Grimm, D. S. No. 71. A knife sticks in their back. See 10.).

When domestic sprites sometimes appear in the form of snakes, it is in connection with the belief genii or spirits who preserve the life and health of certain individuals. This subject, from the lack of adequate sources, cannot be satisfactorily followed up ; though so much is certain, that as, according to the Roman idea, the genius has the form of a snake, so, according to the German belief, this creature was in general the symbol of the soul and of spirits. Hence it is that in the popular traditions much is related of snakes which resembles the traditions of domestic sprites. Under this head we bring the tradition, that in every house there are two snakes, a male and a female, whose life depends on that of the master or mistress of the family. They do not make their appearance until these die, and then die with them. Other traditions tell of snakes that live together with a child, whom they watch in the cradle, eat and drink with it. If the snake is killed, the child declines and dies shortly after. In general, snakes bring luck to the house in which they take up their abode, and milk is placed for them as for the domestic sprites.

We will now give a slight outline of the externals of divine worship among the heathen Germans. The principal places of worship were, consistently with the general character of the Germans, in the free, open nature. The expression of Tacitus was still applicable; Groves consecrated to the gods are therefore repeatedly mentioned, and heathen practices in them forbidden. In Lower Saxony, even in the eleventh century, they had to be rooted up, by Bishop Unwan of Bremen, in order totally to extirpate the idolatrous worship. But still more frequently, as places of heathen worship, trees and springs are mentioned, either so that it is forbidden to perform any idolatrous rites at them, or that they are directly stigmatized as objects of heathen veneration. At the same time we are not justified in assuming that a sort of fetish adoration of trees and springs existed among them, and that their religious rites were unconnected with the idea of divine or semidivine beings, to whom they offered adoration ; for the entire character of the testimonies cited in the note sufficiently proves that through them the externals only of the pagan worship have been transmitted to us, the motives of which the transmitters either did not or would not know. As sacred spots, at which offerings to the gods were made, those places were particularly used where there were trees and springs. The trees were sacred to the gods, adoraverit. The prohibitions in the decrees of the councils and the laws usually join trees with springs, or trees, springs, rocks and crossways together. Whether all the passages which refer to Gaul are applicable to German heathenism is not always certain, as trees and springs were held sacred also by the Kelts, whose festivals were solemnized near or under them; an instance of which is the oak sacred to Jupiter, which Boniface caused to be felled. These trees, as we shall presently see, were, at the sacrificial feasts, used for the purpose of hanging on them either the animals sacrificed or their hides, whence the Langobardish Blood-Tree derives its name. Similar was the case with regard to the springs at which offerings were made; they were also sacred to the god whose worship was there celebrated, as is confirmed by the circumstance, that certain springs in Germany were named after gods and were situated near their sanctuaries. How far these were needful in sacrificial ceremonies, and in what manner they were used, we know not. But the worship of trees and springs may in reality have consisted in a veneration offered to the spirits who, according to the popular faith, had their dwelling in them; tradition having preserved many tales of beings that inhabited the woods and waters, and many traces of such veneration being still extant, of which we shall speak here after. It seems, however, probable that the worship of such spirits, who stood in a subordinate relation to the gods, was not so prominent and glaring that it was deemed necessary to issue such repeated prohibitions against it. This double explanation applies equally to the third locality at which heathen rites were celebrated stones and rocks ( can certainly have been only a grove. The fourth chapter of the Indiculus,; De casulis, i.e. fanis,; may refer to small buildings, in which probably sacrificial utensils or sacred symbols were kept).

In stones, according to the popular belief, the dwarfs had their abode ; but principally rugged stone altars are thereby understood, such as still exist in many parts of Germany. We are unable to say with certainty whether the beforementioned offering-places served at the same time as burying-grounds of the dead, a supposition rendered probable by the number of urns containing ashes, which are often found on spots supposed to have been formerly consecrated to heathen worship. But the graves of the dead, at all events, seem designated as offering-places. That such offerings at graves were sometimes made to the souls of the departed, who after death were venerated as higher and beneficent beings, may be assumed from the numerous prohibitions, by the Christian church, against offering to saints, and regarding the dead indiscriminately as holy; although not all the sacrificia mortuorum and the heathen observances, which at a later period took place at burials , may have had reference to the dead, but may also have had the gods for object. Hence we may safely conclude that all the heathen rites, which were performed at springs, stones and other places, had a threefold reference: their object being either the gods, the subordinate elementary spirits, or the dead; but in no wise were life less objects of nature held in veneration by our forefathers for their own sakes alone.

Northen Mythology, comprising the principal traditions and superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and The Netherlands. Compiled from original and other sources, in three volumes. Vol I of III, By Benjamin Thorpe,

Continued in part 2.

Pic. Source:

1. http://deutschland-im-mittelalter.de/Kuenste/Literatur/Nibelungen/Lindwurm-Kampf

2. http://www.artoftheprint.com/artistpages/zdrasila_adolf_rubezahl.htm

3. A. Rackham

4. https://pixers.us/wall-murals/germanic-nordic-gods-freya-wotan-thor-52026588

5. https://worldhistory.us/european-history/the-norse-god-tiwaz-or-tyr-and-the-origin-of-tuesday.php

6.https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/tuisto-or-tuisco-is-the-divine-ancestor-of-the-germanic-peoples-lc990127-0192-1

7. https://i2.wp.com/www.jassa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/incubusz.jpg

8. A. Rackham

9. ib.

10.ib.

11.ib.

12.ib.

13. https://pierangelo-boog.blogspot.com/2017/08/ernst-liebenauer-illustrationen-fur_28.html

Pic. Source:

1. http://deutschland-im-mittelalter.de/Kuenste/Literatur/Nibelungen/Lindwurm-Kampf

2. http://www.artoftheprint.com/artistpages/zdrasila_adolf_rubezahl.htm

3. A. Rackham

4. https://pixers.us/wall-murals/germanic-nordic-gods-freya-wotan-thor-52026588

5. https://worldhistory.us/european-history/the-norse-god-tiwaz-or-tyr-and-the-origin-of-tuesday.php

6.https://www.magnoliabox.com/products/tuisto-or-tuisco-is-the-divine-ancestor-of-the-germanic-peoples-lc990127-0192-1

7. https://i2.wp.com/www.jassa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/incubusz.jpg

8. A. Rackham

9. ib.

10.ib.

11.ib.

12.ib.

13. https://pierangelo-boog.blogspot.com/2017/08/ernst-liebenauer-illustrationen-fur_28.html